The most intense rush I feel when I hike occurs just beyond halfway up to the summit, when I know that the trailhead’s well behind me and the peak’s a long way off. When I’m losing the safety nets of modern life — cars, roads, medicine, hospitals — right when I might need them the most. My brain tells me to be scared. Go back. But it also tells me to be joyful. Keep going. I feel both intimidated and liberated.

The moment’s duality is no fluke. It’s biological. The brain processes uncertainty in two ways simultaneously. First, it creates fear with adrenaline and an assortment of 30 other hormones. In animals, this is universal and necessary for survival. Second, it analyzes the uncertainty. If evidence suggests everything will probably be OK, we can choose fight over flight. This, in turn, seems to trigger parts of the brain associated with pleasure, which explains why some people like public speaking, roller coasters, the movie Saw II, and hiking.

The intensity of this rush, of course, varies with the moment’s peril. What I feel while hiking is a mere trace of what my grandfather felt at the Battle of the Bulge, on the precipice of frostbite and being shot at. But the chemistry is universal. We have all felt this combination of intimidation and liberation, and so has everyone throughout history. Those feelings connect us to the past in a palpable way. Mozart felt it when he moved to Vienna at 26 to compose, despite mediocre prospects. Crew members on Ponce de Leon’s ship Santiago were washed with the same chemicals as they approached the New World. When he crossed the Rubicon and marched to Rome, Julius Caesar must have experienced this same adrenaline-fueled mix of fear and excitement.

If he were real, Odysseus may have felt the most intense rush of us all. In Book 12 of Homer’s epic, Odysseus’ starving crew — already short six members who were eaten by the six-headed Scylla – defies the Sun God Helios Hyperion by hunting the deity’s immortal cattle for food. Helios calls on his friend Zeus who, after toying with the crew for a week, smites them. Only Odysseus survives, but he’s blown back to the impossible-to-navigate Strait of Messina, the narrows where Scylla lives just across from twin peril Charybdis. It’s the original rock-and-a-hard-place.

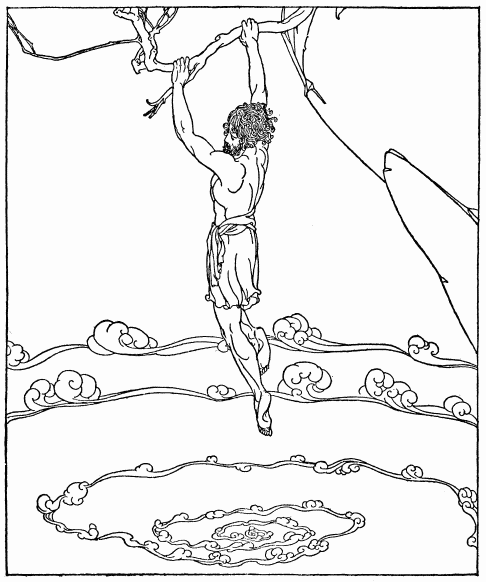

Odysseus avoids doom by hanging on to the roots of a fig tree atop one of the cliffs above Charybdis. It’s the original cliffhanger.

It’s hard to imagine any situation that would produce a more intense rush than what Odysseus would have felt. Perhaps that’s why the word that we use still today to describe that mixed rush of fear and excitement comes from this scene in this story.[1]

Odysseus clung to the fig tree’s roots, the ριζα in ancient Greek, transcribed as rhiza or rhizikon. Even today a rhizome is a type of root. But rhiza also came to mean cliff, and, eventually, it gained the metaphorical meaning “difficulty to avoid in the sea” as the root came to symbolize the precarious situation Odysseus found himself in.

In Caesar’s Rome, the word became risicum. Latin passed the word to Spanish as riesgo, which to crew members on Santiago had evolved to mean, literally, “to sail into uncharted waters.” Latin also led to the Italian risico, which itself passed on to middle-high-German at the dawn of the Renaissance as rysigo, but by then it had lost its seafaring meaning all together. Rysigo was a word the German-speaking Mozart would know, and could relate to. It was a business term that meant “to dare, to undertake, enterprise, hope for economic success.”

From root to cliff, to difficult seas to uncharted waters, to uncertain business. Ριζα became rhizikon became risicum became riesgo and risico. Risico became rysigo. The French called it risque. Having hiked halfway up a mountain, in my body, I can actually feel risk.

With thanks to Rolf Skjong, from whose etymology this story was inspired. ↩︎