When will the Coast Guard get some love?

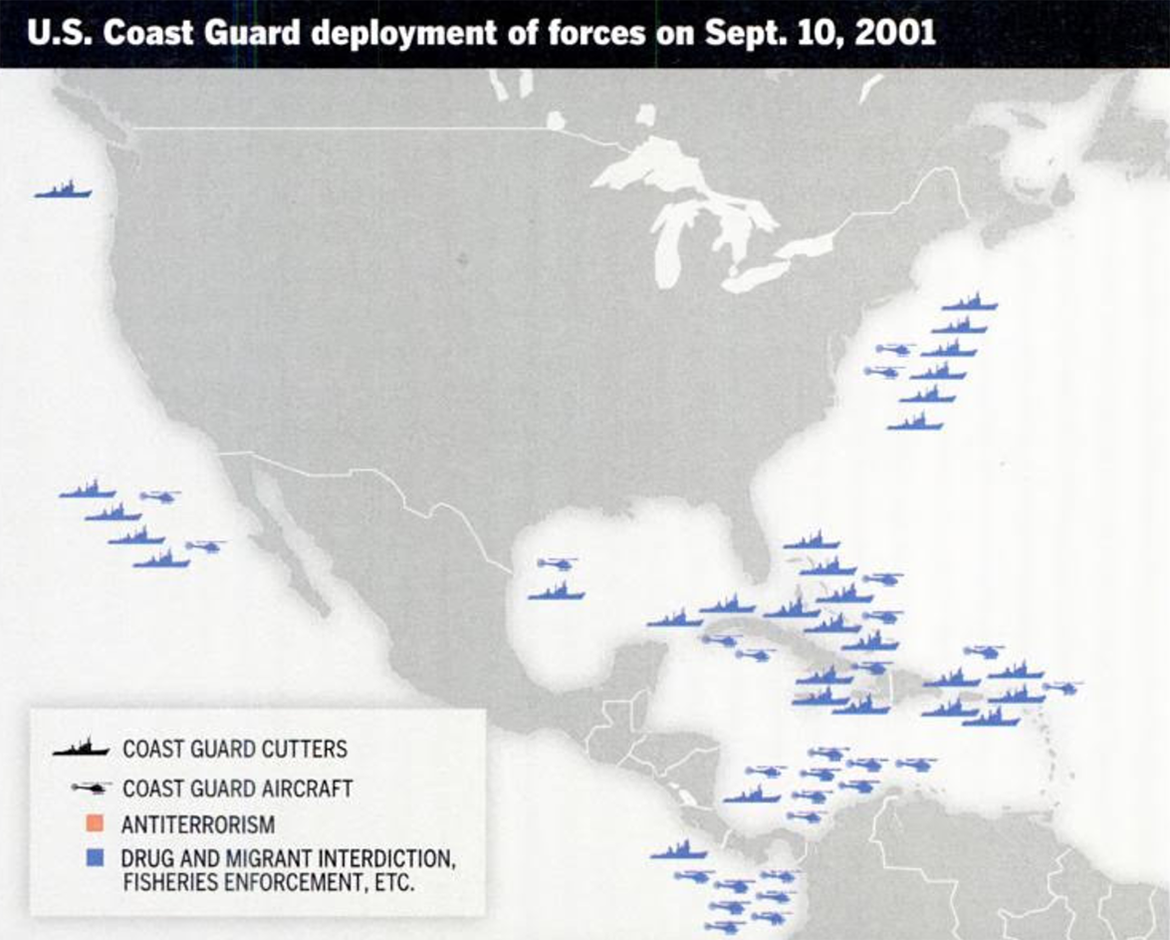

On that awful day, much of the United States Coast Guard's fleet of cutters and aircraft were clustered in the Caribbean, occupied mostly with intercepting illegal drugs and migrants. On a map, the fleet's movement over the next week would look like iron filings sucked in by a continental magnet to the stick to the United States coast. Its primary mission commutated overnight from drugs and migrants to ports and terrorists. Its predominant reputation transposed from a military afterthought-a "backwater," a "stepchild"—to the front line of homeland defense.

Had war been declared, the Coast Guard would have shifted command to serve under the Navy. But the day terrorists attacked, Navy Chief of Operations Adm. Vern Clark instead offered up his Navy to support Commandant Adm. James Loy's Coast Guard. Coast Guard tugboats, buoy tenders, reserves and volunteer auxiliary boats led evacuation and first aid at Ground Zero. By Sept. 12, 2001, a dozen white-hulled cutters patrolled an otherwise empty New York Harbor under piercing blue skies still smirched by rising ash and smoke. By the 19th, most of the Coast Guard's fleet fenced the shores of the Northeast, Florida, the Gulf of Mexico and the long, gentle arc of the Pacific Coast. Even those who know and respect the Coast Guard still talk about that first week with awe. "God bless the Coast Guard," says Rep. Frank LoBiondo (R-N.J.), who chairs the Coast Guard and Marine Transportation congressional subcommittee. Dennis Treece, CSO of Massport, the agency that runs Logan Airport and the Port of Boston, adds, "I don't know who but the Coast Guard could have done what they did."

It was the incarnation of their motto, semper paratus. Always ready. Except that—even in those dramatic days, after that rapid redeployment of forces, the Coast Guard wasn't paratus at all.

"They weren't ready, to be frank," says Bruce Stubbs, a retired Coast Guard captain who is now an analyst at Anteon, a contractor that provides support to the Coast Guard. "No one in the second district [New Orleans] was weapons-qualified. They were limited in their ability to securely communicate with the captain of the port. They moved boats around, but there was no ops plan at the time. Full marks to the Coast Guard," he says. "They were good people making strong, commonsense decisions. It speaks well of them. But they weren't ready."

The Coast Guard is perfectly tailored for the homeland security mission and critical to the Department of Homeland Security's success-and not just because the Coast Guard already happens to patrol 95,000 miles of US shoreline and 3.4 million square miles of US-controlled open seas, through which pass 95% of all goods shipped in and out of the country. More important is the fact that the Coast Guard is uniquely matched to counter the threats that DHS was created to manage, because it encompasses both the military power and law enforcement capabilities required to fight terrorism.

Its heritage of relative poverty means the Coast Guard has long had to do what other military and law enforcement agencies haven't: balance resources using risk analysis, which experts will tell you also happens to be a critical tool to combat an asymmetric threat like terrorism. It's no coincidence that the Coast Guard was put near the top of every proposed structure for a new cabinet-level security department; nor that, when DHS was formed, the Coast Guard became one of only two agencies with direct-line reporting to DHS Secretary Tom Ridge (the Secret Service is the other).

But as much as DHS needs the Coast Guard, the Coast Guard needs an agency like DHS lest it fall into permanent disrepair.

This is why the Coast Guard wasn't ready as its fleet raced north across 30-degrees north latitude after 9/11: It was the seventh largest coast guard in the world, yet its fleet ranked 39th out of 41 in average age. A few of its cutters were commissioned for World War II and many more were children of the 1960s. Its recapitalization project to modernize the boats and planes was in jeopardy of losing its funding. Its operations budget had been cut by 15 percent, even as its workload increased. Search-and-rescuers averaged 84-hour workweeks. And the Coast Guard was coming off a previous fiscal year in which it essentially ran out of gas money.

Coasties joked that since they were constantly being asked to do more and more with less and less, eventually someone would ask them to do everything with nothing. Only it never was entirely a joke. Given their prideful, earnestly do-good work ethic, Coasties would try to do everything with nothing before doing what any other Washington agency in their situation would do: fail. Coasties don't whine and complain and demand the resources they need. It is a noble flaw that has, at various moments in the Coast Guard's history, teetered the agency on the brink of falling apart.

Loy himself compared the pre-9/11 Coast Guard to a "knife dulled by complacency and overuse." The agency wasn't really semper paratus, he said, but rather semper volens. Always willing.

DHS, though, presented a proverbial win-win: The nation would get a top-notch agency to secure ports, harbors and waterways; in return, the Coast Guard would get from the nation—via DHS—the respect and resources needed to manage not only its security mission, but its myriad other missions as well.

The Coast Guard's prospects got even better when Loy became number two at DHS. Finally, in a post-9/11 world, the Coast Guard seemed poised to thrive. It could exploit a favorable direct-line reporting structure and exploit Loy himself to break the Coast Guard's long tradition of doing whatever was asked without adequate resources.

But instead, DHS is reinforcing that tradition, not breaking it. Resources have indeed risen, but not nearly enough, according to observers. That's obviously bad for the Coast Guard, but it's even worse for maritime security, where the stakes are too high to try to do everything with nothing.

The United States Coast Guard is the accretion of five maritime agencies founded at various moments during the country's first century. They are the U.S. Lighthouse Service, in 1789; the Revenue Marine, in 1790; what would become the Steamboat Inspection Service, in 1838; the U.S. Life-Saving Service, in 1878 (set up to rescue wayward sailors); and, in 1884, the Bureau of Navigation (perhaps to help sailors navigate better so they wouldn't become wayward). The five agencies would mutate, adjust, join and commingle until 1948, when the Coast Guard officially took over all of it.

There is something Forrest Gumpian about the Coast Guard's presence in American history-always a witness to major events but never the focus of them. The Revenue Marine fired the first naval shot of the Civil War. In 1886, the U.S. Lighthouse Service arrived on Bedloe's Island to manage the first electric lighthouse, commonly known as the Statue of Liberty. Life-Saving Service workers assisted the Wrights at Kitty Hawk in 1903. Cutters patrolled the North Atlantic for icebergs in 1913 and searched fruitlessly for Amelia Earhart in 1937. Coast Guard Flotilla 10 landed troops on Omaha Beach. Arnold Palmer enlisted in 1950 (but kept golfing). Coasties helped secure space shuttle Columbia's maiden voyage in 1981. They were the first on the scene after Bligh Reef flayed the hull of the Exxon Valdez. They brought Elian Gonzalez to American shores. Recently, they assisted space shuttle Columbia again, this time somberly skimming the Gulf Coast for its debris.

The Coast Guard brought troops to Omaha Beach

The Coast Guard brought troops to Omaha Beach

The name Coast Guard was born in 1915 when the Revenue Marine, by then known as the Revenue Cutter Service, and the Life-Saving Service combined. Its role in waterway security was defined the following year—specifically at 2:08 a.m. on July 30, 1916—when foreign terrorists attacked the United States for the first time. German saboteurs gained access to the wharf on Black Tom Island in New York Harbor, where munitions were being transferred to British ships. The Germans set a boxcar on fire, which set off a chain reaction of massive explosions that continued until dawn, which revealed a sky smirched with smoke and ash.

The Black Tom incident led to the Espionage Act of 1917 and gave the Coast Guard broad sway over U.S. waters and defined port security for the next 60 years, says Dennis Bryant, senior counsel at Holland & Knight, former attorney with the Coast Guard and author of an essay on the Black Tom incident.

The security role, though, would ebb and flow with peace and war for the rest of the century. On Sept. 10, 2001, security was only 2 percent of the Coast Guard's mission.

From dockside, the Coast Guard's changed affiliation—from the Department of Transportation to DHS—appeared to come off like a well-drilled vertical insertion, whereby Coasties drop out of helicopters on ropes during hurricanes to rescue sailors in distress.

The Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002 (MTSA) unified and streamlined security regulations for all maritime stakeholders and gave the Coast Guard its broadest authority yet. Post haste, the Coast Guard produced a Maritime Strategy for Homeland Security under new Commandant Adm. Thomas Collins. The Coast Guard set up a dozen (and counting) Maritime Safety and Security Teams (MSSTs)—small SWAT-like teams contracted out for ship arrivals and other events requiring maritime security, such as the forthcoming Democratic and Republican national conventions.

According to observers, the Coast Guard didn't suffer from the infighting that marked the transitions of quasi-competitive agencies, such as Customs and Border Protection. And it didn't suffer whiplash from a radical shift in focus either, the way the Federal Emergency Management Agency did when it morphed its view from local to federal.

Chief of Staff Vice Adm. Thad Allen, who led the transition attributed its success to the agency's multimission, dual military-civilian charters-what he calls the "genius of the Coast Guard." Coasties call it semper flexus. Always bending.

According to Capt. Daniel May, commanding officer of Group Boston, semper flexus is what allowed the Coast Guard to shift from a mission of 2 percent security to nearly 60 percent right after 9/11, and eventually settle to about 20 percent, where it is now. The Coast Guard revitalized the Marine Safety Office, or MSO. Pre-9/11, MSO was responsible for port safety and waterway management. If you've seen fireworks near water, MSO was probably there. MSO was maligned and separated from operations. One Coastie, Lt. Tamara Pelletier, says that while she was on a cutter, she told her commanding officer that she was going to join MSO. "He wrote me off," she says. But now MSO is the key to enforcing MTSA and making waterway security a success through its Maritime Homeland Security office.

This tack has relied heavily on retraining Coasties, who were welding and cleaning up pollution, to pick up guns and inspect ships. But that's semper flexus. Coasties are expected to be jacks of any number of trades: sailor, inspector, search-and-rescuer, law enforcement agent, EMT. All of the above.

Semper flexus extends to the Coast Guard's fleet. Just take an inventory of the boats docked at the Coast Guard pier in Boston, a mishmash flotilla adaptable for any number of missions. There's a 41-foot utility boat from the 1960s, capable of handling almost any of the Coast Guard's missions, but old, expensive and due to be replaced. Next to that is a brand-new 25-foot Response Boat-Homeland Security (RBHS) with twin outboard engines. Coasties love the orange-hulled RBHS because it goes fast and turns tight. It can't go in deep water, but it can go in a C-130 jet for transport. It's the future of the Coast Guard's port security mission, but it's designed for law enforcement too. Next to that is a 27-foot Boston Whaler, of all things, improvisationally refitted for harbor patrols and vessel escorts. It's a stopgap, the brainchild of a vice admiral with the unlikely name of Jim Hull. Looming downstage is the 270-foot Medium-Endurance Cutter, Seneca, carrying a full cargo of lore, from search-and-rescue adventures to drug and migrant interdictions. However, it has lately become part of the homeland security mission as well. At the bow of the Seneca sits one Rigid Hull Inflatable (RHI), a fast boat that was originally designed to chase down drug runners, and Coasties love it nearly as much as the RBHS. However, it's used so much that it has become a maintenance millstone. On port side, there's a motor surf boat that will soon be replaced by another RHI, since the motor surf boat performs the way it looks, like a tub.

Coast Guard Cutter Seneca in Boston, part of the aging fleet

Coast Guard Cutter Seneca in Boston, part of the aging fleet

In 1998, the Coast Guard launched an ambitious $20 billion, 30-year plan—the Integrated Deepwater System project—to modernize this hoary, motley fleet of cutters and aircraft.

Deepwater was never really embraced. In fact, President Clinton commissioned a "Roles and Missions" study the next year to see just what it was the Coast Guard did. "I think the hope was, quietly, that it would find that the Coast Guard was sort of expendable," says Scott Truver, group vice president with Anteon who has analyzed the Coast Guard for 30 years. "The administration wanted to downplay its importance; the Office of Management and Budget wanted to slash its funds. They were hoping the report would say 'Just forget Deepwater, break up the Coast Guard and divvy up the missions.'"

The report, issued in 2000, turned into hagiography and instead suggested that if the Coast Guard didn't exist, it would need to be invented. The Coast Guard was called "one of the most efficient agencies in government" and "a unique instrument of national policy." Moreover, it said that Deepwater should be a "national priority that should move forward expeditiously and without interruption." Presciently, the report implored the government to "rebuild" the Coast Guard to "hedge against tomorrow's uncertainties" including "terrorist activities." It concluded: "America will need a Coast Guard capable of operating alongside the other U.S. armed services to support the nation's security strategies and policies."

Yet within a year, the General Accounting Office went the other way entirely and criticized Deepwater so severely that the program looked as if "it may be reduced to yet another piecemeal, stop-and-shop program," National Defense magazine wrote. GAO didn't argue that the Coast Guard didn't need to modernize-it was impossible to argue that. Rather, it said that the kind of money that the Coast Guard demanded for modernization wasn't realistic. It was $500 million per year. Put into perspective, that was one percent of DoT's budget at the time, less than the rest of the military spends cleaning up pollution at its own bases, or the same amount of money the Coast Guard seizes in drugs every 52 days.

Deepwater was resuscitated and even given a jolt after 9/11. It is slated for nearly $700 million in 2005, but then again, in the DHS era, $700 million turns out to be not enough. After all, security as a Coast Guard mission has increased 1,220% in terms of resource hours, from 19,000 hours pre-9/11 to 254,640 last year. And Deepwater's timetable is not practicable for combating terrorism's immediate threat.

Rep. LoBiondo said he wants to step up investment in Deepwater and compress the timetable, largely because investing sooner, rather than spreading it out over decades, could save as much as $6 billion in interest payments and equipment maintenance costs. Days after LoBiondo made this observation, however, the GAO issued two more reports that voiced serious concerns over the Coast Guard's ability to manage Deepwater, even at the current pace, because the Coast Guard can't afford to hire more people to manage it.

Michael O'Hanlon of the Brookings Institution estimates that homeland security has increased the Coast Guard's workload by 25 percent, but personnel, while rising, has not increased in kind. "It's not even close," says O'Hanlon. "There's no match whatsoever between the missions and the resources."

O'Hanlon says that the Coast Guard needs at least 20 percent more money-something closer to $9 billion per year instead of $7 billion. He says, "It's hard to imagine $2 billion more wouldn't get a hearing," given the mission at hand. After all, the Navy will spend $20 billion-almost three times the entire Coast Guard budget-just buying boats and airplanes in 2005.

In other words, DHS, a cabinet department focused almost exclusively on security and anti-terrorism, has failed to fight for a credible level of resources for the agency that it has charged with what is arguably one of the country's greatest weaknesses-maritime security.

DHS's shortcomings in this regard were crystallized recently when a Senate panel rejected a measure to raise a much needed $400 million for port security through users' fees. That, despite the fact that the panel agreed that the Coast Guard doesn't have all of the $7.4 billion it needs to enforce MTSA and that port security thus far is underfunded.

"Forget the money; Congress isn't going to give them any more money," says Bryant. "They've made that abundantly clear." Should they? "Yes." Why won't they? "Because cargo doesn't vote. People do. And people fly in airplanes."

USCG Medium Endurance Cutter Acushnet. Decommissioned, March 11, 2011. Commissioned, October 26, 1942, as USS Shackle for the United States Navy

USCG Medium Endurance Cutter Acushnet. Decommissioned, March 11, 2011. Commissioned, October 26, 1942, as USS Shackle for the United States Navy

For 2005, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) budget was increased 20% to the Coast Guard's 7%. The Coast Guard's budget is still slightly higher than TSA's but then again, security is all that TSA does while it's only 20 percent of what the Coast Guard does. Drugs still get smuggled across the Caribbean. Migrants still try to steal entry into the United States. Oil gets spilled. Sailors still tack into the teeth of biting storms. Ice still chokes commercial waterways, and then when it melts in the spring, floods them.

These missions don't disappear, but they suffer. Illegal drug interdiction resource hours, according to the GAO, are down 44 percent, from about 122,000 hours pre-9/11 to 69,000 last year. Search-and-rescue is down from 83,000 to 64,000 hours. Domestic fisheries enforcement dropped from 91,000 to 67,000 hours. Other missions have spiked, like migrant interdiction (up 81 percent), ice breaking (up 44 percent) and defense readiness (up 518 percent). The GAO says it's not clear the Coast Guard has figured out how to balance all these fluctuating parts with its resources.

In the meantime, while defending the maritime homeland, the Coast Guard sent its largest contingent of personnel overseas-to Iraq-since the Vietnam War. Then secured the port at Guantanamo Bay. Then went to Haiti. Semper nixus. Always straining.

"I have major concerns," says Margaret Wrightson of the GAO, "about the huge challenges still facing the Coast Guard. We asked for a strategic action plan from the Coast Guard a year and a half ago that would lay out how they plan to balance their many missions, and what level of resources they need for them. We still don't have it.

"I will say this," she adds. "The Coast Guard has some of the finest people I've ever met in government. So far they've risen to the occasion with respect to homeland security. But we need that plan. I don't think they're stalling. They're struggling. There's still a sincere struggle at the Coast Guard to figure it out."

Coasties use one other unofficial motto, borrowed from the Marines: *Semper Gumby*, a reference to the pliant green claymation figure. *Semper Gumby* is *semper paratus* reflected off of a funhouse mirror. It's confidence, professionalism, politeness, adaptability, efficiency and bravery, all warped by resigned frustration. Gumby is flexible, and also bent by other people. *Semper Gumby* has been notoriously translated by Coast Guard search-and-rescuer personnel as "We have to go out, but we don't have to come back."

The day I visited the Coast Guard in Boston, the agency was busy interdicting hundreds of Haitian migrants. And looking at 69 ships queued up in the Gulf of Mexico pointing north, and 47 vessels on the Mississippi River pointing south, they were working frantically to reopen the lower river where a vessel had sunk and was blocking the way.

The Coast Guard also continued to prepare for a July 1 deadline to review vessel security plans, which would include a costly inspection process for international vessels for which Congress didn't appropriate any money.

Also on that day, Ridge presented DHS's proposed budget to the Senate, which included the inadequate increases for the Coast Guard along with astonishing increases for TSA and other efforts. Project Bioshield, a bioterrorism defense program got $2.5 billion, a 186 percent year over year increase. GAO continued to prepare its reports that would publicly criticize the Coast Guard's ability to manage Deepwater. And Petty Officer Andrew Shinn, who was escorting me, explained why we couldn't go out into the harbor as we'd planned, despite the fact that it was a bright, calm winter day.

He said that each boat is given a certain number of hours per year for each mission: homeland security, aids to navigation, search-and-rescue, and so forth. It costs $2,162 per hour to operate a 41-foot motor lifeboat, and five months into the fiscal year, Shinn's team had used up its allotted budget. So we just stood there by the refitted Boston Whaler, with no chance of taking it out. Another Coastie who had joined us just in time to hear my dilemma smiled, then said he had to go. And as he walked away, he called back, wryly, "If you figure out the resources thing, call me."[1]

Welp, more than a decade after I wrote this, I searched "Coast Guard funding news" and lo, the first or second link from this week, there's the headline: "Coast Guard Lacks Funds..." Tales of seventy-year old ships, funding shortages, Coasties repairing old boats, and plans for further cuts to budget while the mission remains. Same shit. Different day. ↩︎