The "bared and bended arm" of Massachusetts

The "bared and bended arm" of Massachusetts

Since 1857, Highland Light in Truro, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, had sent out its beacon — a symbol of certitude. But by 1996, the future of the 66-foot tall tower was hardly certain at all. The structure sat on a stretch of coast that, on average, cedes three feet of shoreline to the Atlantic each year. Just 110 feet away from an eroding cliff, the oldest lighthouse on the Cape was in danger of plummeting to a historic death. Something had to be done. So on July 4, 1996, after getting the go-ahead form the U.S. Coast Guard and others, Cape Cod Light was pulled, slowly, 450 feet inland.

The move will keep the lighthouse safe. For now. But on Cape Cod, nothing is truly safe. The peninsula — home to thousands, a vacation getaway for millions, lined up and down with hundreds of miles of competent, sometimes superior, beaches, and beachfront property that could be described the same way — will wear away. Anything too near to the shore will topple into the sea.

The fate of Cape Cod was set when it was formed. About 25,000 years ago the Laurentide Ice Sheet plowed south through what is now eastern Canada — Nova Scotia — and the northeastern reaches of the United States — Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont — scooping up huge boulders and pulverizing fields of rock along the way.

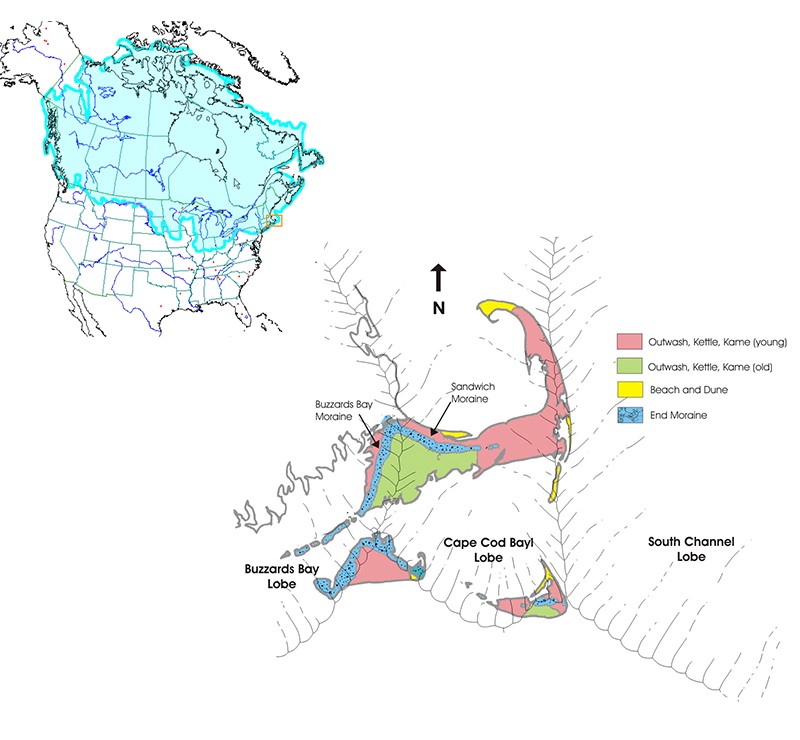

Three lobes at the front of the Laurentide gave the Cape into its unique shape. The Buzzards Bay Lobe advanced across eastern Massachusetts down to the southeast reaching to what is now Martha’s Vineyard, the larger of Massachusetts’ two major islands. From the northeast, down from Maine and across an expanse that’s now ocean, the South Channel lobe plowed down south-south east. Pinched between these lobes, the Cape Cod Lobe bulldozed straight south as far south as what’s now Nantucket.

The Laurentide Ice Sheet near its farthest reach (NOAA). Below, the three lobes at the front of the glacier that plowed material into the Cape and the Islands (USGS).

The Laurentide Ice Sheet near its farthest reach (NOAA). Below, the three lobes at the front of the glacier that plowed material into the Cape and the Islands (USGS).

About 20,000 years ago, that’s where the ice stopped it’s grind across the northern hemisphere and, slowly, began its northward retreat. It took 4,000 years for the ice to recede from the south of Nantucket to just north of what is now Boston. The glacier retreated but the material that had shouldered and tumbled along its front edge stayed. It formed long ridges of soil called moraine, mounds of debris called kames, and blocks of ice, like giant ice cubes that tumbled into lowlands and melted there to form small, deep ponds called kettles.

Although the glacier was receding, and the continent’s outer shorelines had been defined, the current shape of the cape was still not apparent. Since the glacier hadn’t reached back to the poles yet, sea level was much lower than it is today, which exposed much of the continental shelf around the cape. Melt water streams spread sand and smaller gravel called outwash, which formed a broad plain across what is ocean today. If you were there, you could have walked from Hyannis on the mid-Cape to Nantucket through forests and meadows and across beaches. You’d have seen mastodons and mammoths.

Each of the three lobes helped to carve out that unmistakable shape of the Cape. The Buzzards Bay Lobe withdrew across what is now Plymouth and shaped the Cape’s thick western shoulder. The middle Cape Cod Lobe got locked up with the outermost South Channel Lobe and together they tossed around a wide field debris that became the Cape’s elbow.

The outermost South Channel Lobe defined the upright forearm that now faces the open sea on the east and cradles Cape Cod Bay on the west. It melted last. Trapped between that ice, freshly formed highlands to the west, and recently deposited moraines to the south the Cape Cod Lobe melted. For maybe 1,000 years, Cape Cod Bay was a giant freshwater lake.

For a thousand years, trapped glacial melt water formed a fresh water lake where Cape Cod Bay is today. (USGS)

For a thousand years, trapped glacial melt water formed a fresh water lake where Cape Cod Bay is today. (USGS)

The future Cape Cod existed, but only as high inland elevations of a blunt peninsula. Slowly, the surrounding lowlands drowned as the glacier disappeared and oceans began a steady upsurge. By about 6,000 years ago, 14 millennia after the Laurentide Ice Sheet had begun its retreat, the only land still above sea level would have looked roughly like what we see today, that arm, described by Thoreau with a perfect grace and wit:

Cape Cod is the bared and bended arm of Massachusetts: the shoulder is at Buzzard’s Bay; the elbow, or crazy-bone, at Cape Mallebarre; the wrist at Truro; and the sandy fist at Provincetown, — behind which the State stands on her guard, with her back to the Green Mountains, and her feet planted on the floor of the ocean, like an athlete protecting her Bay, — boxing with northeast storms, and, ever and anon, heaving up her Atlantic adversary from the lap of earth, — ready to thrust forward her other fist, which keeps guard the while upon her breast at Cape Ann.

Since then, wind, wave attack, and longshore currents have taken over the job of shaping the land. Like a potter’s hands on clay, these forces constantly push material, mostly sand, from one place and redeposit it down the coast as new land. Stretches of sand called barrier spits are evidence of the process. They grow as an extension of a beach when currents carry material from one spot to another.

Spits reshape with the tides, currents, and sea level, adapting to preserve themselves. On Cape Cod, the wearing away and building up of sand is as inevitable as the western sun sinking under First Encounter Beach in Eastham every night. As wind and wave sweep away the coast near Truro on the outer reaches of the Cape, the Atlantic longshore currents pick up the material and redeposit the sand near Provincetown, the Cape’s northern tip, it’s curled fist.

The wind also builds up land by blowing it inland where it accrues as dunes — some reaching 100 feet high. Seeds get blown there, too, to form a thick, stabilizing network of vegetation and a perch for any number of birds to nest.

The dunes, the shoreline in general, is effortlessly beautiful. The painter Edward Hopper spent many summers in Truro and when you stand on a bay side beach, the water flat calm on one side, and sheer 60-foot dunes, windswept grass, and scrub pines on the other side glowing in low sunlight, you begin to understand why his paintings look the way they do. You are in one.

People want to protect this from nature’s work. They build reinforcements like jetties, piles of rock that protrude from their waterfront property out into the ocean to deflect the current. Geologists disapprove, because jetties interrupt that natural transfer of sand from one spot to another. They stop new land from forming.

As geologists see it, nature doesn’t need our help wreaking havoc. Spits and shorelines are no match for weather. Nor’easters — large storms that get stuck over New England and churn away with high winds and high seas, are the most damaging. Unlike fast-moving hurricanes that lash southern shorelines for a few hours as they speed by, nor’easters will mercilessly batter the Cape for days.

One storm was doing just that in 1987 when the high seas became too much for the barrier spit near Chatham, near the Cape’s elbow. Rogue waves cut open the spit and the ocean rushed to flood the space behind it. Once a barrier breaks, little can be done to stop wave attack from pounding the previously protected beach. The shore is gobbled up quickly. Chatham’s ’87 breach took many houses and boats and permanently change the map.

To those who lost property, it’s cold comfort knowing that this episode was just one of thousands. Chatham alone has suffered at least four massive breaches in 400 years.

The process of erosion must be accepted. In a human lifetime, moving a lighthouse back works. It protects it. But in geological time, it’s just a breath’s delay of the inevitable. Highland Light is merely scraps of wood on a fragile strip of land. In a few thousand years, all that will remain of Cape Cod, according to the U.S. Geological survey, are a few sandy islands and shoals.

Highland Light, and a path to its original site, close to the abrading edge of Truro, on Cape Cod Bay.

Highland Light, and a path to its original site, close to the abrading edge of Truro, on Cape Cod Bay.

Then again, geologists also expect that another ice age is coming — perhaps within 10,000 years. One could picture a massive glacier carving through North America again, bulldozing south, grinding up earth and carrying it along, again. Eventually, the ice would grind to a halt, again. Slowly, the glacier would release its load, creating new kames, kettles and moraines, again. Sea levels would rise, again. And somewhere south of what we call the Gulf of Maine, a sandy peninsula may take shape again. Foamy waves and wind would sculpt the shoreline, again.

And the peninsula would begin wearing away, again.