Copper, China and Crystal Meth. Inside the metal theft epidemic[1]

In a decaying corner of Detroit, behind a box store, along a trash-strewn scrape of urban ruins, surrounded by trees that are either dead or sag like they wish they were, thick black smoke rises against a gray sky. It’s Halloween afternoon, and Michael Lynch, head of security for the utility DTE Energy, in shined black shoes, a dark suit offset by a crisp blue shirt and a bright, patterned tie, is cutting through the blighted patch, following his eyes, and his nose, toward the smoke.

Metal thieves, Lynch knows, burn off the insulation that sheathes the copper wires that carry his company’s product—electricity—because often that’s how scrap yards want to buy it, without insulation. But also, that’s where the name of the company the wire was stolen from would be. At any rate, the sheathing is petroleum-based. Burning it creates an unmistakable cloud that smells like a car accident. Police have made major busts when they happened to see or smell this smoke.

Recalling the events of that day, Lynch says he isn’t setting out to track down a metal theft. He is out in the field with one of his investigators looking for examples of torn-down power lines for a local TV news crew that wants to do a story on metal theft. But while he's out there, a DTE customer says that thieves have stolen wires off the poles in front of his house, cutting off the power. The customer adds that he thinks the thieves are burning the wire nearby, and he points the way.

The intelligence is sound. Lynch finds a column of flames six feet high rising from a dilapidated cement slab. Tending the fire is a thin man in brown pants, a hooded sweatshirt the color of wine and a gray baseball cap pulled low over his goateed face. Lynch is not normally in the field, so he doesn't think about the danger of confronting a man who could be high or armed, or both. Lynch's arrival (and probably his wardrobe—this was no cop) startles the thin man, but luckily he shows few signs of aggression. Lynch begins to ask questions politely. Where'd the wire come from? How much do you have? Where is the rest of it? Where do you sell it? How much do you make

As Lynch receives answers that range from useful to obfuscatory, he hears a rushing noise below his heels. He looks down and is startled to spot a black hose shooting water along the ground. Lynch grabs the hose and aims it at the fire.

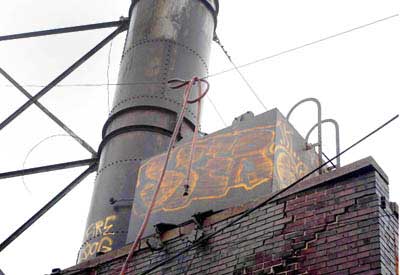

Later, Lynch would put it all together. What he had found was a regular burn site for metal thieves. In fact, it is the perfect burn site, with a concrete surface to burn on and available running water to control and put out fires. Also, the site is surrounded by metal to steal. A nearby communications tower had already been looted so much that, at one point, 911 service was knocked out. Plus, there is a scrap yard nearby where the stolen metal can be sold. If the yard refuses, other buyers are available close by. For 50 cents on the dollar, Lynch says, you can walk up to them with a grocery cart full of any metal, without ID, and sell it no questions asked. The entire supply side of the metal theft economy is within walking distance of the fire Lynch is dousing.

Soon the fire's gone. With only pungent gray smoke crawling away now, Lynch directs the column of water spilling from the hose to land on a tangle of red wires that, from a distance, look like the entrails of roadkill. Even without sheathing to positively identify them, he thinks they're DTE wires. "It's like knowing you're looking at a Chevy," Lynch says, "even though someone took the emblems off." An investigator who is with Lynch calls the police and then snaps a photograph of the improbable scene; the thin man in dark clothes, less than a yard away from Lynch, protests angrily. Lynch, in his smart suit, his preternaturally blue shirt, is wielding the hose and saying something back, but he's not looking at the thin man. He's looking at the metal.

Confrontation. Michael Lynch gets a tip and finds a copper theft operation

Confrontation. Michael Lynch gets a tip and finds a copper theft operation

Lynch asked the man: Where'd it come from? How much is there? Where's the rest of it?

The metal theft problem affects not just utilities but all companies that have infrastructure, which is just about all companies. If you have a metal fence, it's at risk of being stolen. If you have construction sites, metal will be taken from them. If you have unguarded rural outposts, they will be raided. No metal is safe.

The Laws of Domestic Supply and Chinese Demand

China needs metal, and junkies need crystal meth. Where these two facts intersect, there's metal theft.

These two facts intersect every day, everywhere. Thieves are risking their lives and others' for metal. They yank down live copper power lines and remove grounding wires from electrical substations, rail lines and wind farms. They snatch wire and plumbing from new housing and business park construction sites, or sometimes from existing houses. In Detroit, The Kronk Gym, a legendary boxing basement where heavyweight champ Tommy Hearns once sparred, was already on the ropes financially; when thieves stripped it of all its copper pipes, The Kronk closed for good. A statue known as the Battle Cross, commemorating the war on terrorism, was snatched from its stand in Yakima, Wash. "Reclining Figure," a 2.1-ton sculpture by artist Henry Moore, was stolen from a museum in England. At auction, the sculpture was worth $5 million. As scrap metal, it would fetch maybe $10,000.

The wire and the damage done.

The wire and the damage done.

Thieves with a chain and a truck will pull down municipal light poles to get the copper wire out. They'll get a chain saw or a Sawzall or an ax, and cut down a utility pole. If they don't have any of those, they'll climb the pole. In any of these cases, they'll leave behind $5,000 of damage to extract a few hundred dollars' worth of copper. No metal is sacred: Cemetery memorials are snatched, and so are the roofs of churches. Wherever there is metal—copper in particular but also aluminum, zinc, nickel and bronze—there is someone stealing metal to sell it for a little cash to support themselves or their drug habit. It is the most significant physical security concern today.

It's basic economics: Demand for metal is long and supply is short, making semiprecious metals precious. Precious to China, where a growing nation will pay high prices for it, and precious to addicts who need a hit. Investors can't get enough commodity metal, and neither can the impoverished looking for a quick buck.

How Copper Became Trendy

At 5:10 a.m. on Oct. 9, 2003, in West Papua, Indonesia, one of the walls of the Grasberg copper and gold mine collapsed. Two million three hundred thousand tons of rock rushed down into the open pit, killing eight and injuring five. Copper prices spiked.

The prices had already been rising for a few months. It was June 2003 when copper and other metals finally started to show signs of life after falling to historic lows in early 2002, when copper dropped to 65 cents a pound on the London Metals Exchange. But by mid-2003, investors had started talking about a place they called "emerging Asia," which includes China, India and other countries. Most of the focus is on China, with its 20 percent economic growth rate, says Patricia Mohr, an economist specializing in metals at Scotiabank. "Investment funds began to recognize that China was emerging as a major force," she says.

Demand for metal was picking up in Europe and America too, as new construction continued and the military machine warmed up for a coming war in Iraq. After years in the doldrums, the four key base metals—aluminum, copper, nickel and zinc—became hot commodities, with the bellwether red metal, copper, especially hot. After the Grasberg landslide, copper quickly passed $1 per pound.

At the time, Michael Assante was head of security at American Electric Power. He tracked prices weekly and briefed executives quarterly on metal theft incidents and total loss. "We could map the rise in prices to increased security incidents. For the most part it was a direct correlation," he says.

Prices climbed steadily. Then workers went on strike at the El Abra mine in Chile in late 2004, and by 2005, prices passed $2 a pound. But no matter how high metal prices climbed, it seemed, China kept buying. China became the world's biggest consumer of the four key base metals, by a wide margin, virtually overnight, Mohr says. Money flowed toward metal, copper in particular. Investors who once put only precious metals in their portfolio were adding semiprecious metals and creating index funds out of commodities once considered too volatile. Metals became a way to diversify a portfolio, since trends in commodities don't necessarily follow the stock market.

Copper hit $3 a pound by early 2006. China kept buying. The mines and the mills had basically taken the '90s off from creating new mining and smelting capacity because prices were so low for so long and then flagged after 9/11. Without new capacity, the world entered a "deficit condition" where copper production fell below consumption.

Copper hit $3 a pound. China kept buying.

"We've had a 100 percent increase in metal thefts year over year," says Mike Dunn, manager of physical security at American Electric Power, based in Ohio and serving electricity in 10 Midwestern and Southern states. At both meetings of the Edison Electrical Institute trade association last year, Dunn says, all anyone could talk about was metal theft. In Tucson, Ariz., metal theft is up 150 percent. In Dallas in 2006 there were 1,500 cases of metal theft reported through August, according to a Dallas Observer article quoting police. Last spring, police in Hawaii opened 15 separate metal theft investigations in two months. Lynch at DTE in Detroit adds, "We had one facility that had 38 [incidents of breaking and entering] in eight months." Thieves keep coming back to the same sites, often rural ones where it will take police a long time to respond. "At these prices, it's worse than ever before," says Theo Lane, a senior coordinator with Duke Energy, which provides electricity in the Carolinas. "We've seen cases where thieves will sell their stolen metal to a scrap yard, then steal it from that yard to sell it again someplace else." Assante calls metal theft "a plague."

On May 12, 2006, copper hit $3.99 per pound, nearly $8,800 per metric ton, a figure that causes Mohr to say, simply, "Extraordinary!"

China finally balked. Some companies there felt prices were too high. Many relied on metal inventory acquired for just this situation. At the same time that China started refusing to pay $4 per pound, construction in the United States slowed as the housing market softened. The Federal Reserve held steady on interest rates, and Mohr says that investors are speculating rates might start dropping again in 2007. Investors started cashing out. Copper prices started to fall, and no one was sure how fast and how hard they would come down.

Not too fast and not too hard, it turns out. Seven months after the $3.99 peak, copper remains above $3 per pound (at $3.03 as of Jan. 8), and Mohr says that the growth in copper prices has slowed, but zinc and nickel remain at record highs. China, Mohr says, is not going away. She believes copper will be lower in 2007, but adds, "even if copper falls to, say, $2.50 per pound, that's still historically very lucrative."

Even if prices drop, metal theft will remain historically high. Thieves have caught on: There's metal everywhere and much of it is, understandably, unguarded. Aluminum guardrails. Brass fittings. Bronze plaques. Aluminum siding. Sprinkler fittings. Catalytic converters on church vans. Bronze urns. Storm drain grates. Street signs. Copper downspouts. The nozzles on Houston's fire trucks' hoses. All of those have been reported stolen. You don't notice how much metal there is for the taking until it starts getting taken. And, Lane says, "There's no end in sight."

Where 800 Pounds of Stolen Copper Goes

For Lane, metal theft is problem number one. "Matter of fact," he says, "this morning we arrested six guys in connection with a substation break-in." The men allegedly stole about 800 pounds of copper wire on one of those large wooden spools waiting to be used as electrical wiring at a Duke Energy construction site in Anderson, S.C.

Once a spool like that is stolen, thieves will cut the wire into 4- or 5-foot sections, effectively destroying the product for the owner. At that point, it's scrap. Then comes a crude burning process, usually throwing the wires directly into a fire. Burn sites, like the one Lynch found in Detroit, are reused. Lane says some thieves will coat the wires with oil or other accelerant, load them in a 55-gallon drum and drop in a lit match. Other times, oak wood is put in the bottom of a drum and sections of wire are dropped in like lengths of raw spaghetti.

Loose scrap and bales await a buyer in a scrapyard

Loose scrap and bales await a buyer in a scrapyard

That's what the six men Lane was talking about were allegedly doing when a patrol officer saw, and smelled, black smoke coming from behind a house outside of town, in an area suspected of metal theft activity. The men were charged with grand larceny, but Lane says finding them was luck.

Imagine if the police hadn't happened onto the scene. This is what might have happened: The thieves would have finished burning the insulation and hosed down the wires, piled the charred copper into a truck and headed for the scrap yard.

Many businesses have contracts with the local scrap yard. These six men would be peddlers—unknown and unaffiliated. Some yards, says Steve Solomon, who owns Solomon Metals, a scrap yard in Massachusetts, won't deal with peddlers, so the thieves will send in someone else who the yard can trust. If the thieves are known around town or have reason to worry they might be discovered (all sources said you need an ID to sell any significant amount of metal) or suspect someone has reported their metal stolen to the scrap yard, they will travel two counties over to another scrap yard, says Lane.

Say the scrap yard agrees to buy the stolen scrap. If the price of copper is $3 per pound at the time, the peddler will get quite a bit less than that, perhaps 60 to 75 cents on the dollar, depending on several factors, says Bryan McGannon, a spokesman for the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI), a trade association for scrap yards. Those factors include the quality of the scrap, size of the haul and the region of the country. In this case, the 800 pounds of copper stolen from Duke Energy is off-the-spool, industrial-grade copper. The dealer agrees to pay $2.50 a pound for the copper and hands over $2,000 in cash to the peddler. "Not bad for an hour's work," Lane says. "Why would you break into a house or a store?"

If the scrap dealer, suspicious, refuses to buy the copper, the thieves will seek out a gray market dealer with lower standards and fewer questions. Lynch at DTE has discovered such rackets and says the thieves would get considerably less cash, maybe 50 cents on the dollar or less, $1.50 a pound if they're lucky. (That still yields $1,000.) The gray market dealer will then have to sell to another scrap yard that trusts him, for the higher rate of $2.50. Several sources describing this market said the dealer might split up the haul and sell it to other dealers or directly to a metal manufacturer.

However the metal gets to a legitimate scrap yard, the dealer adds the 800 pounds of stolen metal onto a pile of high-quality copper scrap, one of many piles sorted by metal type and quality. Legitimization of the stolen metal has begun; the stolen scrap and the honest scrap are mixed into a pile or compressed together into a bale, like hay.

The scrap yard sells the bales and other sorted scrap to metal manufacturers, tons at a time, for something closer to the $3 per pound going rate, maybe $2.75. The metal manufacturers then mill it. It's smelted. The stolen copper and honest copper are liquefied and amalgamated, swirled together as one. Out of this process, says ISRI's McGannon, comes copper cathode—the commodity that's trading at $3 per pound on the London Metals Exchange. Cathode is sheets or bars of copper, like red gold. The copper manufacturers sell the cathode to companies in emerging Asia for near the going rate, $3 per pound. At the local port, the small city of containers that have just been emptied of their bric-a-brac stamped "Made in China" are reloaded with the copper cathode, put back on the boats and sent to markets around the globe.

Copper meant to carry electricity across the Carolinas might now carry hot water through a new high rise in Shanghai

In China, the companies that bought the metal extrude it, turn it into products, probably wires or plumbing, and sell it to a contractor there. The contractor brings it to a construction site. The stolen metal's journey is over. The 800 pounds of industrial grade copper wires that were meant to carry electricity across South Carolina are now part of pipes carrying hot water to a lavatory on the 37th floor of a fantastic new high-rise in Shanghai.

How the Drug Problem Got to Be Mike Dunn's Problem

Smoking or injecting methamphetamine produces a flash of unregulated pleasure—dopamine floods the brain—that lasts up to 12 hours. Snorting or ingesting it produces euphoria, relatively less intense than a flash but a high that will last as much as a day, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). One form of methamphetamine, crystal meth, also known by names like ice, crank, glass, and tina, effectively combines the two. It creates a rush and a high.

As with cocaine, another stimulant, users of crystal meth are highly alert; they don't need sleep. Appetite decreases while activity increases. But crystal meth stays in the system 12 times longer than cocaine. With all that time and energy, high users can set about procuring the funds that will get them more crystal meth. They can, for example, break into an electrical substation to take grounding wires and other metal to sell at a scrap yard for cash.

To combat the theft of copper grounds from substations, Dunn at American Electric Power says his company replaced the all-copper grounds with ones that consisted of copper wound around galvanized metal, known as copperweld. The idea was to remove the value of the target; copperweld is worth far less than pure copper grounds. And unwinding the copper from the cheap metal rod, Dunn says, would take hours.

Nevertheless, as soon as he put such a ground in, it was stolen. "They had to have been in there for hours for what? A hundred bucks of copper?" says Dunn.

Some metal thefts like this at first seem bizarre—Herculean efforts put forth for minimal payoff. But they make sense when put in the context of crystal meth. Meth addicts have been known to go on intense and repetitive activity sprees like cleaning a floor with a toothbrush. Carefully unwinding copper seems leisurely by comparison.

Yank or climb, anything to get the red gold.

Yank or climb, anything to get the red gold.

Dunn also recalls a rural stretch where someone apparently went utility pole to utility pole cutting off the grounding wire running down the side of the pole as high as the thief could reach, for miles. News stories and authorities from other regions cite further examples: In Arizona, someone climbed a pole and reeled in 4,400 feet of copper wire (a very heavy load) before, apparently, falling off the pole and fleeing, injured, with the wire. In Ohio, 400 feet of aluminum bleachers was nabbed. Three men in Russia used a blowtorch to cut 5-foot sections of narrow-gauge rail from a train line. By the time they were caught, they had cut and hauled 50 tons of it. In one week in the Ukraine, a museum's historic 14.5-ton locomotive was stolen and cut up for scrap, and so was an 11-meter metal bridge, the only road in and out of a town.

A single high dose of crystal meth has been shown to damage nerve terminals in the brains of animals, as have long periods of lower doses. The more one uses meth, the more one needs to use it. Addiction comes rapidly and leads to hard-to-fathom binges. A gram of crystal meth could last a week when you start; on a binge, an addict might take a gram every three hours for several days, without sleep or food, according to NIDA. Addicts become violent and confused and eventually exhibit clinically psychotic symptoms, like paranoia, hallucinations and something called "formication"—the sensation of insects crawling all over the skin.

When addicts stop using crystal meth, they don't suffer physical withdrawal symptoms like the shakes. Instead they are left with depression, fatigue and a craving so intense that they will take extreme measures—climbing utility poles carrying deadly amounts of live electricity, say—to get more.

It's hard for someone sober to comprehend the craving, says Joe Frascella, the director of the Division of Clinical Neuroscience and Behavioral Research at NIDA. To try, he says, imagine holding your breath for one minute. "You get to a point, near the end, where all you can think about is taking a breath," he says. "You're in a panic state. A drive state. Nothing else matters except breathing." In a sense, Frascella says, craving crystal meth is not unlike living in the moment before you drown, for days on end.

It's important to point out that not all meth addicts are metal thieves and, likewise, not all metal thefts track back to meth addicts. No scientific data exists yet that confirms the link between the two, but security experts and law enforcement say the link exists. Many interviewed for this story mentioned the drug unprompted. Indeed, hot spots of crystal meth abuse—Hawaii, the Southwest, San Diego, Oregon, and increasingly the rural Midwest and South—map to hot spots of metal theft. In local news stories, law enforcement officers make the connection explicit. "Anytime you've got copper thefts, you've got meth problems," said Dakota County Sheriff Don Gudmundson in a September story in the St. Paul Pioneer Press. "One goes with the other." In one Detroit case, officers found a house full of stolen metal and several people living there. One man was shooting up when they found him and asked to finish before they arrested him. "We know drugs are the driving force," says Dunn, who is a retired commander of a narcotics unit in Texas. "I don't think people are stealing copper to buy groceries. I really don't."

More Than Collateral Damage

The link between addicts and metal theft also explains the irrationality behind some of the riskiest metal thefts and their consequences. Thieves may be dishonest, but they are also rational. A thief interested in making money isn't likely to break into a substation, because the risk of death is so high for a reward of only a few hundred dollars' worth of copper. And yet, substations are getting broken into constantly, and live wires are being cut, utility poles being climbed.

Craving crystal meth is not unlike living in the moment before you drown, for days on end

"Drugs hijack your motivational systems," NIDA's Frascella explains. "Motivation gets pushed so out of whack."

A crystal meth addict, whether high or craving a high, isn't rational about what constitutes risky behavior. He lacks judgment and can't control his motivations. "This habit removes all the inhibitions you normally have with scary environments, including dangerous equipment like an electrical substation," says Pete Jeter, lead physical security specialist at Bonneville Power in Oregon. This is biologically true, according to Frascella, who notes that meth affects inhibitory parts of the brain.

Thus, stories of wildly risky metal thefts that lead to death are legion and often harrowing. "I had two fatalities in a 30-day period," Lane says. "Both were cutting wires off the pole. I think the first guy thought he was cutting a de-energized line. The second one is a real mystery, but who knows? We don't have a witness left."

"We had one in Kentucky up on the pole recently," Dunn says. "He cut the wrong wire, got wrapped up in the lines and just hung there upside down, dead, until someone passed by and noticed." Lynch in Detroit mentions "quite a few deaths recently in the city" including one electrocution when a thief was trying to steal live wires out of a traffic box.

In 2006, Jeter remembers, a man broke into a Clark Public Utilities substation and cut out copper grounding wires. Then he apparently bumped his head against a live wire, at which point he became the grounding wire. Seventy-two hundred volts coursed through him, and he burst into flames. The body burned for 45 minutes while engineers turned off the power and let the energy drain out, until it was safe to go in.

Scrap Man in the Middle

Solomon, owner of Solomon Metals, also president of the New England chapter of ISRI, walks the floor of his warehouse, past 2,500-pound bales of old copper wire, past carburetors compacted together, past barrels full of metal shavings and boxes overflowing with shiny cables, their color so unmistakably unique that it's got the same name as the metal: copper. Solomon's looking at something else, though. Thick industrial wire wrapped in gray insulation and wound around a plastic spool—the kind you'd find on a job site. "You see?" he says. "It could be an electrician who's done with a job and has no place to store the hundred feet of wire left on the spool, so he sells it for scrap."

Solomon is at the tail end of an impassioned defense of his industry, the scrap yards, which he, ISRI and others feel is served far too big a piece of the blame pie for the metal theft problem.

In fact, the scrap yards are kind of the hinge of the metal theft supply chain, the thing that connects the supply side, those stealing and selling scrap, to the demand side, those buying scrap to make it into the new metal. Because of this precarious position, security experts, the police, copper manufacturers, everyone seems to point fingers at the scrap yards as the place to look for both the problem and the potential solution. An uneasy peace reigns between scrap dealers and security executives, especially at the utilities. While they work together, sharing intelligence on thefts and trying to enforce secure practices and awareness of the problem, both sides seem to think that the other could be doing more.

Abandoned brewery; copper theft haven

Abandoned brewery; copper theft haven

"The scrap metal industry is to some degree an illicit market," says Duke Energy's Lane. "You've got legitimate players, no doubt, but also a whole lot of illegitimate players." Lane's comments are echoed by others. A September 2006 article in the Long Island Business News on the topic called scrap yards "an ideal fence" for stolen metal.

Most security executives, like Lane, preface their comments about the scrap industry by saying they understand that most scrap dealers are honest. Jeter cites "extraordinary cooperation" between security teams and scrap dealers. Lynch says some busts in his area have come from tips by scrap yards.

Usually, though, there is a "but." Lynch: But "some are operating on the fringes." Jeter: But "we're talking with county and federal prosecutors about enhanced legislation regulating the scrap industry." Assante: But "the scrap yards know much of what's coming in is stolen, and they buy it anyway."

Part of Solomon's rebuttal includes the fact that his company, like most reputable scrap yards, retains copies of IDs from sellers. It also does not pay cash for metal. ISRI has created a theft alert system so members know what metal has been reported stolen where. ISRI also has published recommended practices for avoiding stolen scrap and set up an awareness program with the National Crime Prevention Council.

More than all that, though, Solomon's rebuttal is the half-used spool of wire. "It's new wire, just like a stolen spool would be. How are you going to tell this from stolen wire? You're not. Wire is wire. Scrap metal is scrap metal. You almost have to go by the character of the person coming in." And even then, Solomon says, inside jobs are common. An employee of a reputable firm may show up, and the scrap dealer would have little reason to distrust him. Can the scrap yards be expected to figure out who's honest and who isn't? "We're not a policing agency," says Solomon. "I tell the security guys, you can't depend on us to be the gatekeeper. I tell them, if you don't want people to take the metal, you've got to start treating it like what it is—an asset."

He also tells them scrap dealers are victims too. Tons of metal is stolen from scrap yards, according to an article in ISRI's magazine, Scrap. In Georgia, 13 tons of used beverage cans. In Pennsylvania, 32,000 pounds of aluminum. More than 50,000 pounds of copper in Tennessee and Louisiana.

The problem, Solomon says, really is the 1 percent of disreputable dealers, "peddler shops," he calls them. No matter what controls scrap dealers put in place, it won't stop the theft, it just moves the transactions to these shops, to a grayer market. Solomon believes the finger-pointing at his industry stems from stereotypes of the scrap industry, which originated mostly from family-owned businesses like his (Solomon Metals was started by his grandfather 62 years ago). People assume they're all peddler shops, a bunch of shady operations.

Still, Solomon says he brought three security executives from utilities to the New England ISRI meeting in December. "We should be working together to fight the problem, not fighting each other. My message to the security industry is that the scrap industry is not trying to be the bad guy. We're doing what we can. We're caught in the middle here."

Beyond Awareness

Of all the techniques DTE's Lynch has employed in Detroit to combat the metal theft epidemic there, perhaps the most effective has been an awareness program that in effect amounts to reminding the police to look up. "They're trained, you know, to look for criminals banging in doors," says Lynch who started the program in 2005. "We just say, look up in the air, and since then we've had more than a dozen arrests made on the poles. That's outstanding."

He bumped his head against a live wire. Seventy-two hundred volts coursed through him, and he burst into flames. The body burned for 45 minutes until it was safe to go in.

Awareness programs for citizens and police, of course, dominate security execs attempts to combat metal theft. Fliers. A media campaign. Meetings with police, city and state officials. Lynch has augmented these efforts with a rewards program—$1,000 for each useful tip. Dunn of American Electric Power has set up a hotline for reporting suspected thefts. Lane at Duke Energy also engages local sheriffs of South Carolina, reminding them of the laws that require dealers to record a legitimate ID for anyone selling more than 25 pounds of scrap. "We've seen times when they'll take a library card for ID," Lane says. "We're also trying to make sure the district attorneys know this needs to be prosecuted as a serious crime. We don't want them to plea-bargain out or dismiss the case." In Oregon, Jeter is doing the same.

Utilities are working on lobbying programs at the state and federal levels that would link metal theft to terrorism through the fact that utilities are considered critical infrastructure. More severe penalties may stem the tide, but some argue that it's not the severity of the penalty that staves off crime, but rather the likelihood of getting caught, which remains low, especially in rural areas. Plus, penalties and chances of getting caught are risk propositions lost on the meth-fueled thief.

Another way companies have sought to win public support is to position metal theft as a public safety issue: Power outages disrupt local economies. Dangerously exposed live wires and ungrounded substations can harm or kill innocent passersby.

As for protecting the assets: Lynch's site after the 38 breaking and entering cases was reinforced with an 8-foot corrugated steel wall trimmed with razor ribbon. So far, it has held up. Others are adding CCTV and intrusion detection systems (as are some scrap yards). But, "It's not practical to consider these measures as an answer," says Dunn. "These fences cost three or four times what a normal fence costs, and I've got 3,800 substations." Assante mentions "dedicated warehouses" that securely store metal, "but that's a lot of cost, and when work is localized, they want the metal [available], not waiting in some central warehouse."

Metal theft, then, has become another risk assessment project: Where are the most significant targets where one needs to invest the extra capital in defenses?

Another technique being considered is marking metal. The ideas range from simply spray-painting the wire to using high-end tools to put microscopic signatures on the metal itself. But this, too, is expensive and it has limited application. After all that marking, the most likely time a company would use it to identify its stolen metal is after it has been chopped up into scrap.

One of the most controversial proposals floated for controlling the metal theft market is a program called "tag and hold," words that make Solomon sneer. "We don't want to go into that," he says. In tag-and-hold programs, scrap yards tag incoming scrap with a unique ID and put out an all-points bulletin on contents of each lot. Then they hold the scrap for a week while security executives, investigators and police look for matches with reports of stolen metal.

Solomon is skeptical. "It's a good idea if you want to shut the scrap industry down," he says, noting that much of his metal moves through the yard in less than a week. Holding it not only would affect his ability to do business—what if prices changed while he was sitting on the metal?—but there isn't the space to hold it. It would be like stopping the middle car of a train while all the cars ahead and behind tried to keep going.

A $1,000 Drop in the Metal Bucket

Back in Detroit, behind the box store, Lynch completely douses the fire, and the thin man in the wine-colored sweatshirt yells at him. But the man does not attack. Defeated, he simply walks away, and Lynch can't stop him. "My sense is he was using the proceeds for drugs," so he probably just wanted to move on to find more proceeds, Lynch says later. He let him go; he had pictures. He gave the pictures to the police who, according to Lynch, found the man and arrested him on suspicion of metal theft.

Lynch returned to the DTE Energy customer who had first provided the burn-site tip to grant him his $1,000 reward. He had given several of these checks before, the first of which went to a Detroit resident who noticed some guys climbing a pole. That tip led to their arrest. Lynch brought along a cameraman that time to capture the classic photo op. In the picture, Lynch beams. The tipster smiles. They shake hands. Lynch hands over the check.

Photo-op. A copper theft tipster gets his $1,000 reward

Photo-op. A copper theft tipster gets his $1,000 reward

But across the street, dead center of the picture, stands a crumbling house. The kind of house, Lynch says, where addicts go to get high, after they've stolen metal and sold it for the cash they need to buy ice. "Metal theft is the number-one issue for us," Lynch says. "With utilities, it's more pressing than terrorism or anything else. This issue, everyone is experiencing it."

I love how this story-which one the Grand Neal Award (the "Pulitzers of the Business Press") for best feature article-connects macro forces to local phenomena. Economics on a global scale affect economics on the street corner. ↩︎