the wail sounds like a wolf’s howl. loons wail to contact each other over long distances. this call is usually heard in the evening

Whitefish Lake is 600 acres, set within the borders of Sylvania Wilderness Preserve. Old growth sugar maples, yellow birch, hemlock and white pine dominate the woods and the greater Ottawa National Forest, which surrounds Sylvania.

On maps, the whole thing is a green splotch that dominates the western corner of Michigan’s upper peninsula, just east of Wisconsin's shoulder. A national forest is one thing--preserved land. A wilderness preserve is another, preserved, protected land. The animals that live here--deer-fox, bear, bald eagles-don’t understand the bureaucratic distinctions, the statutes that disallow machines in a wilderness preserve, including bicycles and portage wheels. In Ottawa, bikes, boats and the ubiquitous jet-ski all co-exist with the environment. If you want to camp in Sylvania, you lug your canoe on your shoulders.

I was with my friends Scott and Nick. After an absurd 8-hour drive up from Madison, we shouldered our canoe and hiked through Sylvania machine-less, feeling we had earned the solitude. And sometime after finding an obvious clearing, back from the water but with silver slivers of lake shining through the trees, we divorced backpacks from sore backs and pitched camp. We'd encounter no other human beings while we were there. We decided Whitefish Lake belonged to us for a week.

Our first night at purple dusk, we did what college kids do. Talked, drank, listened to our fire snap and sizzle. The occasional poke with a stick sent clusters of sparks straight up to be eaten by the night. Then, something new entered into this prosaic scene. The night's stillness was breached by a cry. A long, wailing plea that echoed so that it sounded both near us and also miles away. It was high pitched and hollow, nearly human. The only word that suits it is the cliched one: haunting.

Instinct and movies told us it was a wolf’s howl.[1] It wasn't. And in a moment, the cry was met by more howls. Some sounding closer, some much further away-though maybe those were echoes. The wails shot high above the lake and then sank down through the forest, following an arc not unlike fireworks'. Then, more. A chattering chorus of wildly laughing voices among the howls. We absorbed the conversation, awed by the sounds, the volume of sound. Without realizing it, none of us talked for 15 minutes.

If loons could read maps, they would poke their beaks at the Sylvania green splotch, at all the blue stains in it that are lakes, calling out, Ours. Ours. Ours to claim their territory. They would wail much the way they did that first night we camped at Whitefish.

Loon expert Judith McIntyre explains: “The nocturnal call, they’re communicating with each other when it’s time to, vocally. They can’t see each other, but they recognize each other’s voices. They’re saying, I’m here; don’t come over. I’m here. Okay, I’m here, too. We’re all present and accounted for. They’re taking roll call, and calling mates, they’re setting boundaries. McIntyre calls the behavior territorial re-inforcement messages.

It was an imposing bit of counsel. Despite what we had decided, the lake wasn’t ours.

Last year at Sylvania was an annus horribilis for Gavia immer, the common loon. It marked the nadir of a downward trend in loonling hatchings in the wilderness preserve. A rough line graph of loon births at Sylvania since 1989 looks like the slope of a bluff. Seventeen in 1989. Seven in 1990. Eight. Eight. Seven. Three in 1994. Two last year.

Why? Is it fluctuating water levels? Those fluctuations created by dams and reservoirs wreak havoc elsewhere, but no such structures are here. McIntyre points out that severe weather can have the same effect in Sylvania. “If the water is too high,” researcher Jay Mager says, “the nests are flooded. If the water is too low, the loon might go out fishing, or move to protect the nest from predation, and find it can’t drag its body back up to the nest.” In either case, the adult loon eventually gives up and the nest is abandoned.

To combat that problem, anchored, four-foot square rafts with proper vegetation have been built for loons to nest on. These tiny islands float and so nests always remain a perfect distance from the water. Man-made nests offset man-made dams, or extreme weather. Some of these nests are in Sylvania; some of the cries we heard at night came from them. Still, Mager and others familiar with Sylvania all agree this is not a factor in Sylvania’s low hatching rate.

Other explanations are considred, but none hold up. Low food supply because of high acidity in the lakes? No. Fish abound at Sylvania. Not enough space for the bird, which requires 10-50 acres of lake, but wants even more: never been an issue on Whitefish or any of the loons’ lakes in the preserve. High mercury rates in the loons’ blood: all loons have elevated mercury levels today, and researcher David Evers cautions against simply pointing there. “I’m not sure that alone is affecting the short-term hatching rate at Sylvania.” But the short-term hatching rate is down.

The loon habitat is shrinking. “These are hard times in the southern peripherary. The loons have retreated in some places.” Evers tells me. The southern peripherary is the lower band of loon habitat, which roves over the northern-most United States and southern Canada. Loons were once seen as far south as Illinois, Pennsylvania and California. We’re pushing them northward to Minnesota and New Hampshire and Maine, but mostly to Canada and Alaska. Less solitude, fewer fish to eat and more cottages and boats are some of the constant pressures that have convinced loons the world underneath 43 degrees latitude is no place to live. Judith McIntyre, a pioneer in Loon research and probably America’s foremost expert, calls the invasion of the loon’s space “unintentional but relentless.”

“Looking at activity budgets, productivity is bad, and not just at Sylvania. I guess some populations are steady,” Jay Mager hesitates here because he can’t prove a trend, he can only feel one. In his academic setting at Miami University of Ohio, low reproduction rates demand proof. So he fidgets through facts, “It’s been proven the population has declined this century, of course, but-short term anyway-it appears steady, but I really see the decline continuing in the long run.”

One would think Sylvania’s loon population would be able to thrive, as many of the dangers to nesting loons simply aren't present, like power boats, jet-skis, housing development, busy roads. Human activity here is so limited, the wildlife has free reign of the place. The whole point of a wilderness preserve is just that, preserve the wilderness; create conditions for it to thrive. But the one place loons ought to sustain their numbers, they’re not.

“We had 13 territories, that’s attempts to lay eggs, and that’s about average,” Robert Evans says. Evans is district wildlife biologist for the Forest Service at Ottawa. “But only two loonlings. It wasn’t a very good year.”

Despite all the talk of hard times and declines, a habit which seems to permeate the loon preservation community, Evers says, “the Ottawa Forest population is fledging loons at a sustainable rate.” Paradoxically, “Sylvania isn’t."

When a Hollywood director needs to evoke wilderness, they will film trees. And while you watch wind sifting through the green canopy and some gorgeous light over some water, you will hear the castrato giggle of a loon.

They will use this bit of sound even if the wilderness is far south and nowhere near loon habitats. It works, because, to most of us, loons do represent wilderness. Their presence emboldens us into believing we have escaped our prescribed, technological world, and entered a simpler, more natural state of being, where everything is lovely and birds laugh a carefree laugh. Among the loons, it is easy to fancy oneself as Henry David Thoreau, or some sylvan Puckish creature. Naturalist John Burroughs:

Some birds represent the majesty of nature, like the eagles; others its sweetness and melody, like song birds. The small loon represents its wildness and solitariness.

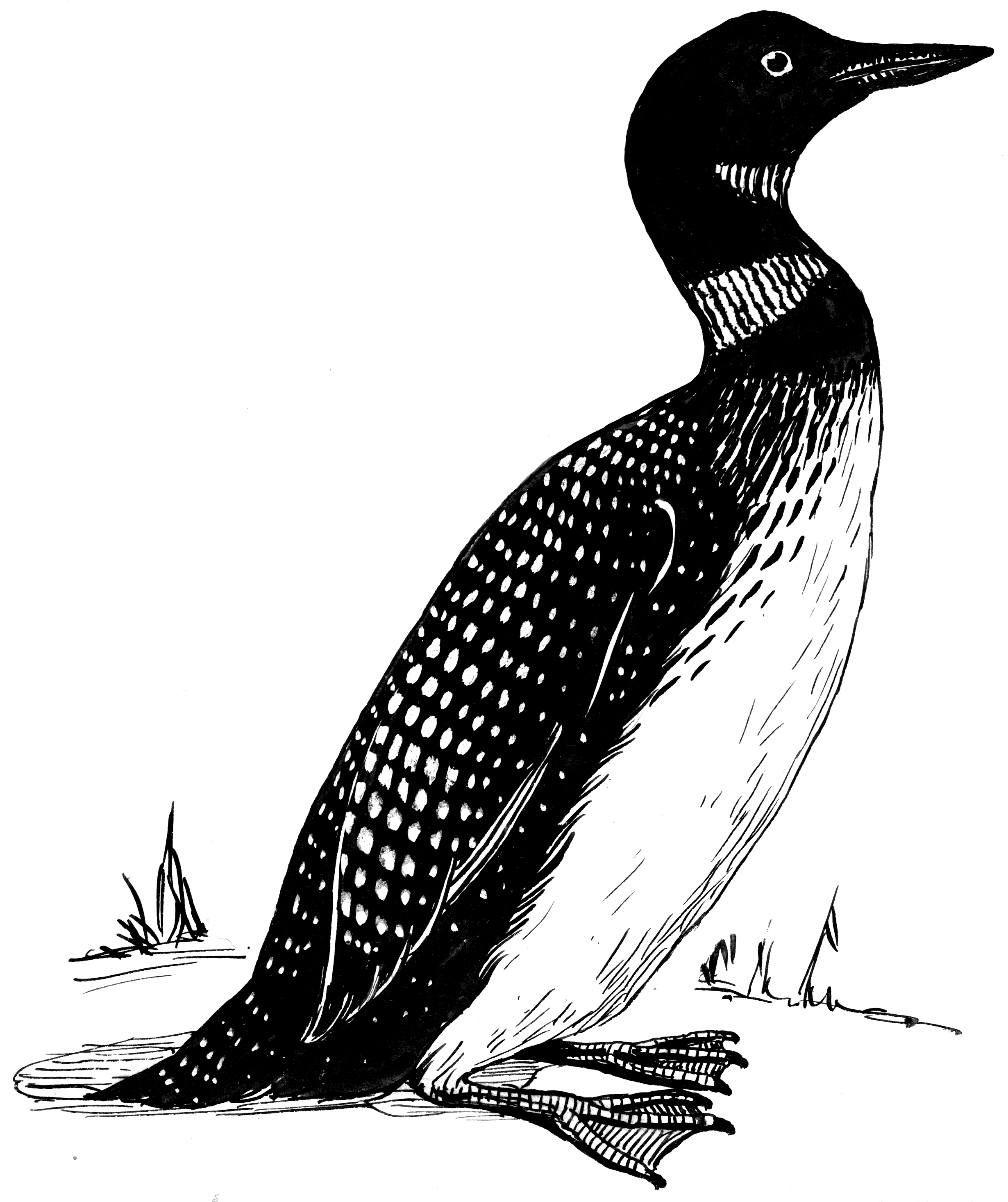

In flight, he’s a heavy, streamlined airbus, wings spread five feet. The loon moves faster than an '86 Plymouth Horizon can. A diving loon is equally attractive. When a friend saw a diving loon, he believed that it looked like a cast iron frying pan. But then he added, “Its long neck and rounded body were graceful, and beautiful, and the speed of him!”

Nature writers, artists, campers have all been drawn by the loon’s elegant appearance, deep red eyes vivid against the velvety black head. Neck collared in white, the white, white breast, with lovely patchworked wings, white and black, tailed by a pointilist scatter of dots.

By John Picken from Chicago, USA (Loon Uploaded by snowmanradio) CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By John Picken from Chicago, USA (Loon Uploaded by snowmanradio) CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

“When you see the loon,” Evers says, “it’s your loon. You are captivated by the loon, that one loon.”

This relationship is venerable. In creation mythology in Scandinavia and North America alike, loons made the earth-or at least they fetched it from the depths of the ocean at the request of God, or Doh (a shaman), or the Great Spirit of the Ojibwa. Loons created land. They can hardly walk on it. They are gawky birds on terra firma, because their feet are tailored to diving, set too far back for a proper gait.

Humans have worn loon skins ornamentally, and have been buried with loons. We have shot them and eaten them. Fisherman have cursed loons because loons are better at fishing.

On Monday, November 3, 1986, dies for a new Canadian coin were loaded up in Ottawa for shipment to Winnipeg. The design would be the voyageur, natives in a canoe, and it would be a one dollar coin. On Thursday, Winnipeg still had no dies. They never found them. A design depicting a loon submitted to the mint in 1978 by artist Robert Carmichael would replace the lost originals. Loons were the new bucks.

Loon. It derives from a term for clumsy. If we were water creatures, the bird’s name would have derived from the phrase effortless grace. They are fluid swimmers, covering long distances quickliy and with an easy agility. Loon. It has come to mean crazy or maniacal, because of the laugh, the cry we cannot resist. Henry David Thoreau documents a loon’s behavior in Walden:

His usual note was this demoniac laughter...but occasionally, when he balked me most successfully and come up a long way off, he uttered a long-drawn unearthly howl, probably more like a wolf than any bird...This was his looning, - perhaps the wildest sound that is ever heard here, making the woods ring far and wide.

“I think the hook is the loon’s calls, they’re so wonderful, they carry so far,” Judith McIntyre says. “But the most surprising thing to people is, most of the time loons aren’t running around doing spectacular things. They’re running a family. They have a very quiet courtship.” But even this behavior is charismatic, their mating dance a lyrical expression of bobbing heads and playful mimicry before they make the awkward, stumbling trip to shore to mate.

The loon has inspired New Hampshire enthusiasts to start a 100-member organization called the Loon Rangers, an intense group set on protecting the bird’s habitat. More than 600 people volunteer to help the Rangers. In New Hampshire, the loon population doubled in two decades, to 594 birds. Similar groups have appeared across the country. It is not an endangered species, yet it's protected ferociously, studied, monitored, because it could be endangered. And because the loon habitat keeps creeping northward, away.

Over and over people told me of their spiritual draw to loons, the way they get into your blood, the spooky fascination with their calls. I understood, having heard the loons’ territorial diatribe at Whitefish; and having sat by water’s edge, when I spied a loon on Whitefish bobbing idly. The loon then slipped under the water’s surface in a graceful splish, and dove deep for food, only to surface minutes later and a hundred yards further away, bobbing idly again. In those quiet minutes, I myself understood the spiritual thing so often alluded to. That was my loon. That one loon.

In Walden, Thoreau chases a loon in his row boat:

I pursued with paddle, and he dived...and again he laughed long and loud...I could not get within half a dozen rods of him...It was a pretty game, played on the smooth surface of the pond, a man against a loon. Suddenly, your adversary’s checker disappears beneath the board, and the problem is to place yours nearest to where his will appear again...he uttered one of those long howls, as if calling on the god of loons to aid him, and immediately there came a wind from the east and rippled the surface, and filled the whole air with misty rain, and I was impressed as if it were the prayer of the loon answered, and his god was angry with me; and so I left him disappearing far away on the tumultuous surface.

Thoreau’s game of checkers probably impaired that loon's ability to reproduce. Jay Mager would call what he was doing people pressure. Robert Evans would call it inappropriate human contact.

“The rangers would go talk to that person and ask him to stop,” Sylvania program manager Mary Rasmussen says. “We would consider that harassing the loons. Thoreau could be ticketed in that case.”

Loons themselves have few predators. Occasionally northern pike will eat loonlings that are learning to dive. Sometimes eagles claw the chicks away. Loon eggs, on the other hand, are in constant peril.

Loon nest with eggs, exposed.

Loon nest with eggs, exposed.

During loon eggs’ 28-day incubation a parent loon leaves the nest to defend it, much as a soccer goalie does not defend from inside the net but in front of it. (Both male and female share equal time incubating). The more aggressively the loon defends, the longer the eggs remain unsheltered.

“I’ve seen loons get scared off nests and not return for a half-hour to an hour. In that time,” Mager says, “cooling threatens the embryo, though the biggest threat to the eggs is predation.” Ravens, raccoons, minks, crows, fishers.

People pressure, the things we do to make loons anxious and leave their nest, enhances a predator’s chances at the eggs. We roar by in water craft laden with horsepower; we glide along shore in a canoe. And we do it in droves. Despite the feeling of solitary peace we felt, Sylvania's big, and other people were in it. Last year, 30,000 visitors spent a day at Sylvania, and 15,000 camped overnight. At any one time, 200 people are camping and another 200 are having a day at Sylvania, with four or six rangers and volunteers on duty.

“There’s an immense amount of people pressure at Sylvania and other places like it.” Mager thinks about Clark Lake in Sylvania. “There’s a small island just out from the canoe landing on Clark, and the loons come there every year but sometimes they don’t even lay eggs, and that could be stress; that could be a people thing too.”

Canoes, unlike power boats, linger about a nesting area. Many campers observe a no landing rule but get far too close to nests to look at the loons, or photograph them. Eventually, when the stress overtakes the loon, it leaves the nest. “We have to emphasize loons more,” Evans says of Sylvania. “We have the no landing rule, from ice off until July 15th, we need to enforce that even more closely.”

The upper peninsula and Ottawa National Forest itself have strong, sustainable fledging rates. It’s only Sylvania that has declined in loonlings. And none of the factors usually associated with low reproduction seem to be at issue, except the pressure of people. “What we’re finding is that a canoe can be even more stressful than a fast motorboat,” Mager says.

Robert Evans agrees. “You know if a camper takes the canoe out, finds a nice spot to drop anchor and cast a fishing line, and it’s near a loon nest -- well that’s not good at all.”

"Mike" Michael L. Baird CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

"Mike" Michael L. Baird CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s called the penguin dance, and if you see it, that’s not good at all.

Maybe a predator lurks near the nest and startled, then agitated the bird. Perhaps, more insidiously, a jet-ski roars around shallow water, and skids by the nest over and over.

Or some college kids glide their canoe across the lake to explore an island.

Their lingering presence causes the bird’s anxiety to intensify. Something is wrong and the common loon knows it, but he will stay there on the nest as long as possible. He will crouch down very low, he will crane his neck. The loon is apprehensive. He hopes you go away.

You do not. And so, like nothing you’ve heard before, he yodels. A long crescendo of shrill, guttural cusses. You notice his red eyes against his opalescent black head. The loon reluctantly leaves its nest and drags its awkward body, and, like a football dropped by the shore, plops into the water.

He faces you head on. Then with feral grace, he lifts himself, juts his white breast and spreads his majestic wings. And the loon dances. He lap-splashes the water, his flippered feet making a ruckus and helping to keep him high above the water line. The ruckus continues with more yodeling, as he holds himself there, showing off his control and power. He presses you for your withdrawal. This is my lake he says. These are my babies.

The penguin dance is as much nervous energy as it is anger. He wants you to retreat because in his nest on the nearby shore, and laid open while he rants are two speckled brown eggs, twice the size of chickens'.

One Sylvania brochure shows a loon. It sails through the middle of the page, amongst the paragraphs. His beak points directly to bolded text:

A maximum of 5 people per campsite is allowed for any purpose at any time.

This is the paradox of the wilderness preserve. We set aside this land to be “wild forever" because we want such places to visit. Places where old growth may grow older and we can come appreciate it. Where wildlife may thrive and we may come to see the wildlife while it's still here. Places like Misty Fiords in Alaska, over two million acres. Like Caribou-Speckled Mountain in Maine, twelve thousand acres. Like Sylvania Wilderness in Michigan, almost twenty thousand acres. In the United States, more than thirty-five million acres of wilderness are protected, pristine, virgin, and they guarantee nothing. Not the success of wildlife, and not the annual summer mating of the common loon at Sylvania. Truly, our remarkable presence, and our romantic affinity for wilderness seems to threaten it.

“Because even though there’s a wilderness preserve, it’s visited by thousands of people and clearly that’s having an effect on the loons,” Robert Evans says.

The loon struggles to remain a presence in the preserve, but outside the legislated nature, and as close as the national forest that surrounds Sylvania, the species enjoys a steady loonling birth rate. It could be that the small geographic area of the preserve, coupled with our desire to get into wilderness and not just a national park, contributes to the paradox.

“Someone has to look at what’s going on there,” says Evers. “It sounds like there’s serious impact on loons from canoeists. And maybe simple management strategies will help.

“Protection of an area doesn’t just make it okay.” Both Evans and Mager agree with Evers. Treating wilderness as real estate does not guarantee a thriving forest or the annual return of the loon.

“We can do a lot of things in one area,” Evans starts, “but we can’t control all the factors that affect them. To me this just points out the need to manage the whole world responsibly, and not just these plots of land.” World management includes educating the people who want to explore the wilderness. When we arrived at Sylvania, we signed forms. We watched a video about responsible camping. Sylvania rangers will intensify these efforts in the coming seasons.

“To you and me,” says Mager, “the loon is the symbol of wild; the feeling of unknown territory. It reflects what’s happening in the wilderness, but also what’s happening to the whole ecosystem. People love loons. The problem is you can love them and want them to be there, but you have to understand them to make sure they stay around. My idea is you can’t look at one site as being the loon’s system. You’ve got to get past geography; there’s a million things going on. It’s great to have wilderness areas, its better than nothing. But hopefully someday, you know...”

Whether you were in Billings, Montana or Bismarck, North Dakota, you're near the top of the United States, but you're still 500 miles south of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, a ten-hour drive. If you made that drive you'd still be 130 miles-two more hours-south of a small unincorporated town called Anglin Lake. If you made it there, you'd probably meet Jack Greening[^2], who lives there.

“I have a little bay here where I want my ashes put, along with my snow white samoyed Missey [short for Mischief]. It’s very beautiful, quiet and peaceful. It’s awkward enough that motor boats can’t get in there, so I pull in, shut off my little nine-horse kicker, and the loons approach. They don’t run away.

“I get closer to loons there than anywhere else. The last three years I had a loon, it came and visited me every morning. I’m 73 and, well, getting a little silly. I’d talk to him, in English, and I’d make loon noises. I feel a spiritual kinship, an unspoken communication. It’s a wonderful relationship. I mean the loon, there’s a natural aloofness to them, but if you treat each other with respect-I mean these guys come right up to me. I don’t think it’s human contact that scares the loons, it’s the excessive human contact that makes them withdraw.”

Greening's a vibrant, semi-retired-but-not-really Canadian who says he can’t complain for an old man. He volunteers care for the wilderness, and the loons. He’s on several environmental advisory committees. He runs a small business. It’s called Jacobsen Bay Outfitters Ltd. and it sits outside the edge of Prince Albert National Park in Christopher Lake, Saskatchewan. He calls it a resort, but he will outfit you with a canoe, maps, camping equipment, a cabin. It’s thirty-five degrees below zero there today, and he has no vacancy.

Jack Greening will show you around because he knows his way around. And because he wants you to respect what he respects: the wilderness, the loons. “Last weekend we had a group come up, and one kid brought a full dog-sled team of eight dogs, and a mushing sleigh.

“I got on the sleigh and we mushed through the forest. You don’t have too many new experiences at my age, but how’s that one?”

Jack Greening

Jack Greening

Anglin Lake is actually five smaller lakes connected by narrows. One of these smaller lakes is Jacobsen Bay. It was named after his wife’s father, Arnie. Arnie was the first to put a cabin up here. Before him, trappers and fishers and hunters moved through the area. A Cree pot and a skull were found at the bottom of Anglin. They were five hundred years old.

Anglin Lake is home to golden perch, red suckers, walleyed pike (“We call 'em pickerel.”), great northern pike (“What we call jack fish or jacks.”) They bite easily. Jay Mager said jacks will eat loonlings that have just entered the water. The lake is shrouded in deciduous white birch, trembling aspen, white spruce, tamarack. “We call a tamarack a larch, it’s the only needle tree that sheds its needles. When it blooms in the spring, it’s lacy, and intricate, and just lovely.

“It’s very exciting and almost a frantic thing, the spring. Trees get leaves, loons do their thing, its part of the season. It’s a hard thing not to stop and watch.”

Above all, the wilderness is about loons to Jack. He will talk at incredible length and with brimming emotion about loons. About the loon that had flown into “witch water,” which is shimmering pavement. The loon waddled helplessly, out of place. Greening helped get the lost bird to lake water, to safety. Jack will mention the “renegades who need 200 horse power so they can water-ski barefoot, and misguided kids with dad’s boat, and the time I found a loon that had been shot with a .22.” But when he tells this last story, he’d rather talk about the beautiful feathers, the intricate patterns of black and white he saw when he retrieved the dead bird. Jack Greening has heard the intimate call of mating loons -- the hoot -- which most people never hear.

You’re never bothering Jack if you want to talk about loons. If you want to talk about jet-skis, you might be bothering him. He always calls them damn jet-skis and he takes on a disaffected monotone. For Jack, jet-skis are to loons what taxes were to Thoreau.

Jack will slight jet-skis and power boats if a crumb of opportunity is there, but he, like the rangers and scientists at Sylvania, understands the threat of people pressure.

“Here at Anglin,” Jack continues, “one of greatest threats is ignorance of public. But with some education, if people get to know this unique and historic bird, they will adapt. We have to respect the loon’s solitude.

Jack tries to educate everybody who stays at Jacobsen Bay Outfitters. He will chatter with guests about the loons, and their behavior around people, and canoes. “If I see a loon, I stop and point it out to the guests, and tell them a story, adding the important information in there too.” He doesn’t lecture. If a resort guest comes to him, and they beam and talk of the dance they saw a loon do for them, Jack explains to the guest what was wrong, and how to avoid it in the future. At his store, in the cabins, pamphlets and other information about the loons are omnipresent.

He modestly refers to all this as education through osmosis.

Last year, Jack Greening received the Parks Canada Award, for his involvement in the Canadian environment. He flew to Quebec and received a plaque from Prime Minister Jean Chretien. The ceremony was at La Mauricie National Park in Quebec, a preserve Chretien helped establish when he was Minister of Parks. The ten recipients of the award boarded what looked like a war canoe with Chretien and then-Minister of Heritage and Parks Michel Dupuy. They drifted over Lac Wapizagonke.

“On the boat, I talked with them. There’s been a lot of changes in the Ministries structure and they’re trying to manage Prince Albert without a superintendent on site. That’s just not going to work, and the Prime Minister agreed with me on a lot of issues, and urged me to correspond with him. But I have not had any return on my correspondence. I’m afraid preservation of national parks takes a second seat to keeping the country together.” Jack sounds at least disappointed in the one-sided exchange, but not resigned. He tells me, direct and unenthused, “Stick to your loons, don’t make this a political debate.”

Of the 150 lakes in the La Mauricie National Park, where Jack received his award, 56 are used by loons. Of those, only 25 are used for breeding. Thirteen to twenty loon pairs summer there.

“It’s funny,” Greening says. “The interest and love of the creature can really overwhelm them. You see that at places like Yellowstone, where the individual’s intentions are good, but collectively, we’re just too overbearing.

“We can’t push them like this,” Jack says.

Recently, researchers have been coming to Anglin Lake, curious to determine whether scientific theory would buoy Jack’s suppositions. They want to know how and why this peaceable, nine-and-a-half mile length of water has supported one hundred loon pairs, which produced sixty two loonlings last year. Jack knows many of the researchers.

“The success?” Greening asks. “Well there’s many factors, but the nature of the lake helps. It’s a large area, but also too shallow for motor boats.” Anglin Lake isn’t very good for recreation, which helps the loons thrive.

But at Lac Wapizagonke, the lake Jack and Prime Minister Chretien sailed together, La Maurice park wildlife specialist Denis Masse said the density of recreation is too high. And the loon, though instinctual and territorial, finally gave up. “We can observe the loon in the summertime,” he said, “we can see the loons but they don’t lay eggs.”

Lac Wapizagonke has been abandoned by the loon.

You can watch the loons return to the Sylvania Wilderness Preserve in early spring, even before ice has wholly melted into choppy, frigid lake water. While the forest thaws into mucky soft earth and a canopy of green emerges overhead, the loons reclaim Sylvania.

Their stunning nightly conversations resume, waggish and haunting as I remember them at Whitefish Lake.

I remember, too, after a quarter-hour of their flurried sound, how suddenly and entirely they stopped. A great ringing silence, punctuated by hissing sap and the odd crack from our fire. The loons had claimed their space. No more need be said. Every night I slept in the wilderness, the same spectacle rang through the forest. A concert for predators, a note to all concerned. It did not occur to me then what the loons cried about. I only thought of how inspiring they sounded.

I only thought of how wondrous it was to sleep there, in the wilderness, close to the loons.

epigraph descriptions of loon calls are from "All About Loons," published by the Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute, Northland College, Ashland, Wisconsin ↩︎