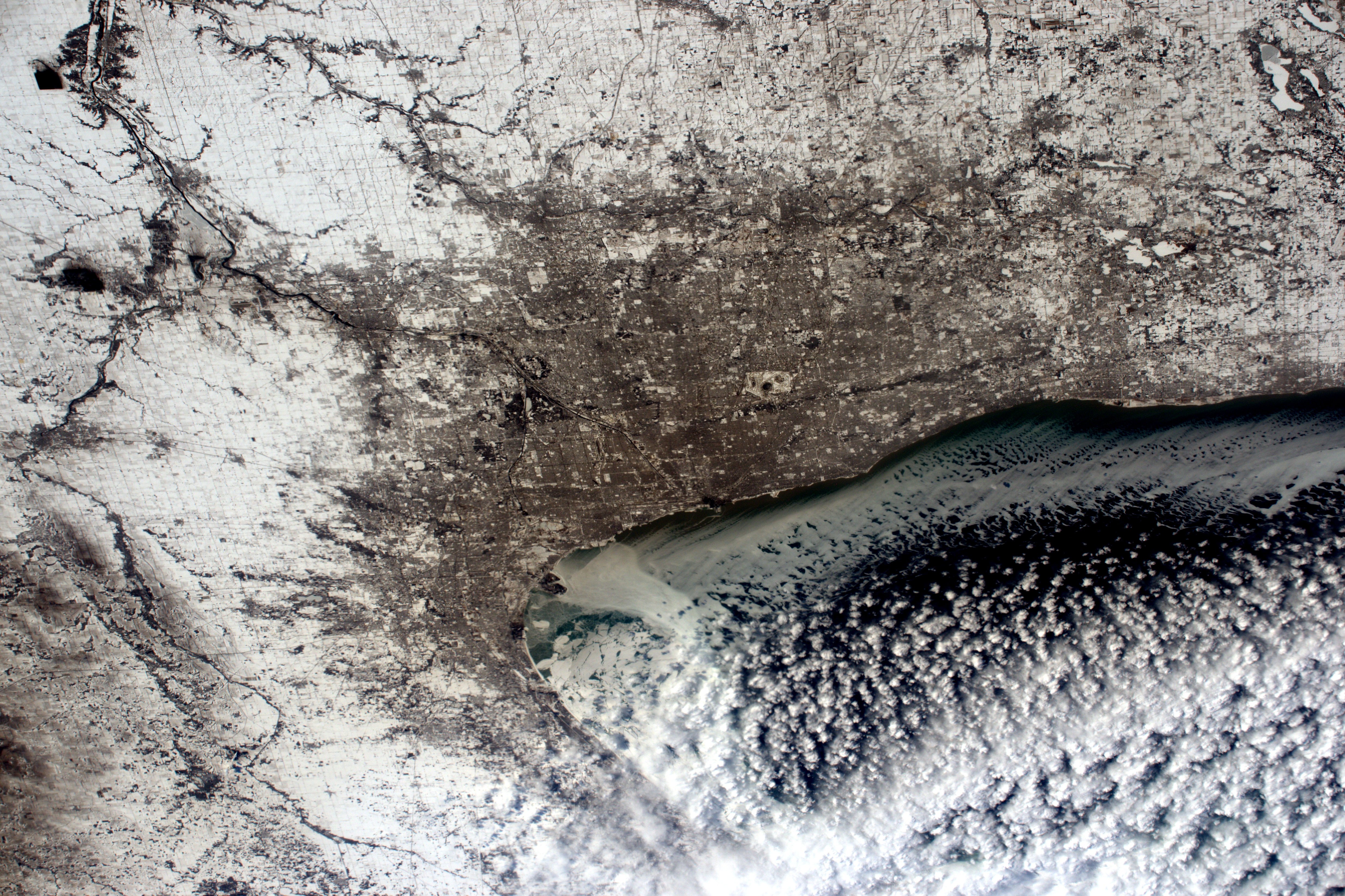

Chicagoland, winter. [NASA]

Chicagoland, winter. [NASA]

It was Dickensian weather. Air that smacked the skin, needles of snow that pricked the cheek, skies grayer than gravestones. It was a hundred years until springtime.[1]

The man I'll call Kevin[2] agreed. "This is the coldest yet," he said, jumping in place outside a coffee shop in Evanston. His brown eyes peeked out from a hood wrapped snuggly around his head. His bulky, dirty winter coat, which served as storage container for many of his possessions, covered several other layers and a thin frame. He pulled two pairs of sweatpants down on his hip to display long underwear. "They're sort of dirty, but they're warm." Thin wool mittens covered chapped hands that he held in fists.

From inside a jacket he carefully pulled a crudely laminated piece of paper that certified his status as a nurse's assistant. He smiled and said he was going to call about a job that week. Then he extracted from his "file cabinet"-a purple Crown Royal bag-his other two prized possessions: a wallet-size portrait of Jesus Christ and a plastic cross that read "GO VES." The "D SA" or the "D LO" in the middle had been rubbed away.

It was late in the afternoon, and Kevin didn't have the $35 a friend charged him for a night's lodging. He had to find somewhere else to stay, and he agreed to show me his alternatives. "The trail is where we go. This is it. I mean, people in Evanston don't even know-Hi, how are you doing?" The passerby gave him a wide berth. "See, they're scared. They think I'm gonna attack them or I'm drunk or I'm a druggie. Sometimes people say to me, 'Fuck you, nigger. I'm not giving you anything because you just gonna shoot it up!' We ain't all like that. I don't hang around that element.

"I used to. I won't lie--why should I? I was strung out. Smoked the pot and listened to-well back then it was Peter Frampton and War and stuff like that. Then you snort something. Then it's coke. Not no more. I've been clean for over two years now, but I don't think of it that way. I just go day by day, you know?"

We turned off Sherman Avenue into the alley behind Barnes & Noble and stopped at a loading dock. Kevin ducked his six-foot frame underneath the wooden ramp and yanked out a small plastic bag. Inside were several disposable razors, a rag that was frozen solid, soap, and cologne. "Here is what I spend my money on, not drugs."

The daylight was waning, and he sighed at the prospect of sleeping under the dock. "Not tonight. It's too cold. Here, I'll show you where else on the trail I sleep."

He took me through the alley and back to Sherman, a block from where we'd started. He said hello to nearly everyone we met and closely inspected some of the women rushing indoors. He noticed one man smoking and said, "Have a quarter for a cigarette?" The smoker replied, "Go to hell."

We moved south on Sherman at a good clip. At a cafe Kevin stopped and pointed through the door. "I've stayed in there," he said, meaning the vestibule. "I know a woman, she stays there a lot, but, you know, not when it's cold like this."

He moved on. "There was a day when you said something to me, we're gonna fight. I'm 35. You get to an age nothing seems to bother you anymore. I just ignore it. All those guys, you know, who say motherfuckin' this and fuck you that. Malcolm X said, 'The reason you cuss so much is 'cause you have nothing to say.' It's true."

We crossed Church Street and swung into another alley with Dumpsters and small loading docks. He pointed to a low roof. "See up there? In the summer we climb up there. It's nice, you know, with the sunsets."

The untrampled powdery snow was now blue in the dusk. "There it is!" he exclaimed. I didn't see anything unusual. But he went up to a flatbed trailer that clearly never moved, lifted a tarp, and climbed under it. Last summer he'd put a foam pad there, but now it was frozen solid.

We kicked through the snow as we headed back toward the street. When we passed the fountains at Davis and Sherman he said, "In the summer we all hang out here on these benches."

He wouldn't say where we were going as we hurried east on Davis. "I've got a girlfriend. She's separated and living with her stepdaughter, so I can't live with her. I walked her to work this morning. She's helping me get back on my feet, too. You know I'm close. Closer than I've been in a long time. I was even working at that Saint Louis Bread Company for a while. But business slowed down, and he had to let me go.

"I'm from Arkansas. I came up here about '87 and was with a girl, you know. But that didn't work out. Like I said, I was in trouble then. Back in Arkansas my family had a lot of land. My dad died, and all his debts, you know-we lost most of the land, but we had a lot. I could ride a horse on all the land we had.

"Gotta be quiet now," he said, pushing his shoulder against a door. We entered an apartment building, and he sauntered through the empty lobby looking less suspicious than I did. We went downstairs into a warm basement. Several of the wooden storage cages contained mattresses, blankets, clothes, and shoes. Some had broken locks and doors. Pointing at them, he whispered, "See, some guys destroy these, and we'll get caught. They ruin it for everyone." He showed off his cage, which had a mattress, a flat pillow, and a tattered blanket. Beside the mattress was a neatly folded towel and another bag of toiletries. "If I can't get the money tonight I'll sleep there probably."

We exited the apartment building undetected. Outside the cold was stunning. "I feel blessed, really," he said. "I'm close to getting it all together. I mean I had dreams that I'd be this great person in the world, but that wasn't to be. I've got to keep going though. I must keep my life going.

"Some days that's hard. You got people yelling nasty things at you, but you know I try to ignore them. 'Cause there ain't no Jewish heaven. There ain't no Oriental heaven. There ain't no black heaven. There's just one heaven for all of us."

We were nearly jogging as we circled back to where we'd started by the coffee shop. Suddenly he looked tired. "Don't ever get here," he said slowly. "Don't lose your self-esteem. Once you slip it's hard to get back. But I'm trying. I'm trying."